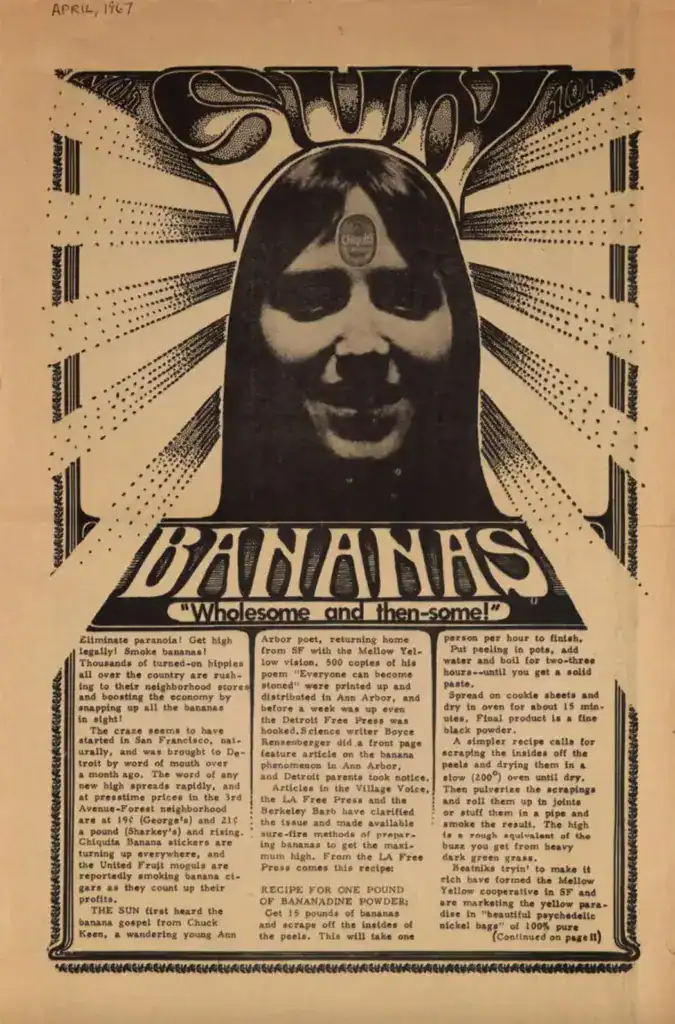

In March 1967, a satirical article about extracting a psychoactive substance called bananadine from banana peels triggered one of the most bizarre drug scares in American history. What started as a counterculture joke in the Berkeley Barb newspaper quickly spiraled into a nationwide phenomenon that had the FDA conducting formal investigations and teenagers across America scraping banana peels in their kitchens.

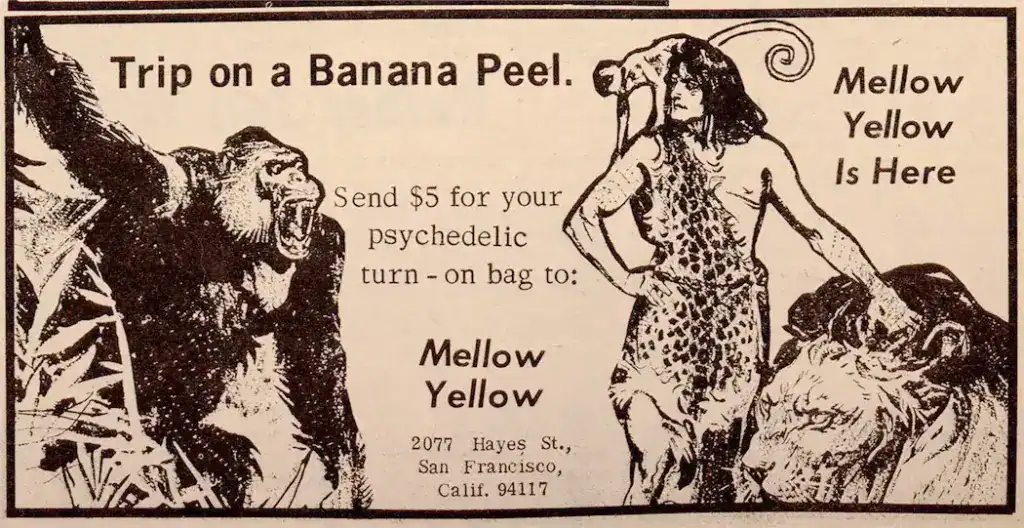

The timing couldn’t have been more perfect. Donovan’s hit song “Mellow Yellow” had recently topped the charts, with many listeners convinced it referenced smoking banana peels. When the Berkeley Barb published detailed instructions for extracting this mysterious compound, thousands of young Americans took the bait. The recipe claimed that by scraping the inner white portion of banana peels, drying it in an oven, and smoking the resulting powder, users could achieve a marijuana-like high.

The Bananadine Recipe Spreads Like Wildfire

Ed Densen, manager of the band Country Joe & the Fish, published the original bananadine recipe as a satirical commentary on drug prohibition laws. The article appeared to come from the San Francisco Oracle, lending it credibility among counterculture readers. Within days, the hoax had spread beyond Berkeley’s hippie community.

Country Joe McDonald later recalled distributing 500 banana joints to his audience during a concert at California Hall. “We told them, ‘It’s banana, it gets you high,'” McDonald remembered. The psychological power of suggestion proved remarkably effective. Concert-goers reported feeling euphoric effects, creating a feedback loop that reinforced the myth’s credibility.

The Berkeley community experienced an immediate banana shortage as eager experimenters bought every available banana from local grocery stores. Students could be seen carrying bags of bananas across campus, their dorm rooms filled with the sweet smell of baking banana peels. The Berkeley Barb had unwittingly created a cultural phenomenon that would soon capture national attention.

Government Panic and the FDA’s Bananadine Investigation

Related article: USS Craven (TB-10): The Cursed Torpedo Boat That Met a Fiery End

The hoax reached the highest levels of government when FDA Commissioner Dr. James Goddard announced a formal investigation in March 1967. “We really don’t know what agent, if there is any, in the smoke produces the reported effect,” Goddard stated, “but we are investigating to see if it might be the methylated form of serotonin.”

The FDA’s response revealed the era’s deep anxiety about youth drug culture. Scientists monitored smoking apparatus for three weeks, conducting extensive chemical analysis on banana peel smoke. Their findings, reported in the Wall Street Journal on May 29, 1967, showed “no detectable quantities of known hallucinogens.” The tests specifically looked for arsenic, serotonin, ergot-like compounds, and adrenergic compounds, all coming back negative at the level of one part per million.

Meanwhile, Congressman Frank Thompson introduced the satirically named “Banana and Other Odd Fruit Disclosure and Reporting Act of 1967.” The proposed legislation would have required “no smoking” stickers on bananas, demonstrating how seriously some officials took the perceived threat. The government’s earnest response to what was essentially a prank highlighted the generational divide and cultural tensions of the late 1960s.

Strange Rituals and Mass Delusion Surrounding Bananadine

The most unsettling aspect of the bananadine phenomenon was how readily people reported experiencing genuine psychoactive effects. UCLA researchers concluded that “the ‘active ingredient’ in bananadine is the psychic suggestibility of the user in the proper setting.” The ritual of preparation – scraping, drying, and smoking – created a powerful placebo effect that many users interpreted as pharmaceutical action.

Eyewitness accounts from the period describe elaborate smoking ceremonies. Groups would gather to collectively prepare their banana peels, sharing techniques and comparing the quality of different banana varieties. Some claimed that green bananas produced stronger effects, while others swore by overripe fruit. The communal aspect of the experience reinforced individual beliefs about the substance’s potency.

Dr. Sidney Cohen, a leading LSD researcher, conducted his own investigation for United Fruit Company. His wife and son spent three days scraping and cooking 150 pounds of bananas to produce 40 ounces of the supposed psychoactive material. Their tests confirmed what the FDA had already discovered – banana peels contained no mind-altering compounds. Yet the myth persisted, with counterculture enthusiasts dismissing scientific debunking as government conspiracy.

The Lasting Legacy of a Psychedelic Prank

The bananadine hoax achieved immortality when William Powell included the recipe in “The Anarchist Cookbook” in 1970, believing the Berkeley Barb article to be legitimate. Powell’s book ensured that new generations would discover the myth, creating periodic revivals of banana peel smoking attempts. The recipe appeared under the scientific-sounding name “Musa sapientum Bananadine,” referencing the banana’s former botanical classification.

Cultural references to the hoax appeared throughout the following decades. A 1971 comic book featured a teenager secretly passing bananas to a zoo gorilla at night, whispering, “Just throw the skins back, man!” Musician David Peel even took his stage name from the banana peel connection, becoming a minor celebrity in New York’s counterculture scene.

The New York Times Magazine reported that during Easter Sunday 1967, “beatniks and students chanted ‘banana-banana’ at a ‘be-in’ in Central Park” while parading with a two-foot wooden banana. These public demonstrations showed how deeply the hoax had penetrated popular culture, creating a shared delusion that transcended individual gullibility.

Today, the bananadine myth continues to surface on social media, with teenagers posting videos of their banana peel smoking experiments. The hoax serves as a fascinating case study in mass suggestion, media manipulation, and the power of counterculture mythology to override scientific evidence. What began as a satirical commentary on drug prohibition became a genuine cultural phenomenon that revealed as much about 1960s America as any legitimate news story of the era.