The Poniatowski Gems represent one of history’s most ambitious art forgery schemes. Prince Stanisław Poniatowski, a wealthy Polish nobleman, commissioned over 2,600 engraved gems in the early 19th century. He passed these works off as genuine classical antiquities for decades. The scandal that followed their exposure devastated the gem collecting market for years.

Prince Poniatowski was once considered the richest man in Europe. He inherited genuine ancient gems from his uncle, King Stanisław August Poniatowski of Poland. These authentic pieces provided the perfect cover for his elaborate deception. The prince used his inherited collection to legitimize the thousands of forgeries he commissioned from contemporary artists.

The Creation of the Poniatowski Gems Collection

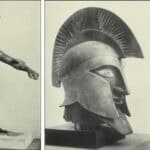

The forged gems depicted scenes from classical mythology and literature. Artists drew inspiration from Homer, Virgil, and Ovid for their intricate carvings. Many pieces featured portraits of famous Greek and Roman figures. The workmanship was exceptional, rivaling the finest ancient examples.

Several talented craftsmen worked on the project. Giovanni Calandrelli created nearly 300 preliminary drawings that survive today in Berlin’s State Museums. Giuseppe Girometti, Niccolò Cerbara, Tommaso Cades, and Antonio Odelli also contributed to the collection. The Staatliche Museen zu Berlin houses many of Calandrelli’s original sketches.

Most gems bore fake signatures of ancient artists. This deception made attribution to specific modern carvers nearly impossible. The consistent style across supposedly different historical periods should have raised red flags. However, Poniatowski’s reputation initially protected the collection from serious scrutiny.

Early Suspicions and Scholarly Doubts

For more strange history, see: Deep State: The Hidden Networks That Shape Government Power Throughout History

By the early 1830s, experts began questioning the gems’ authenticity. Ernst Heinrich Toelken, director of Berlin’s Antiquarium, examined plaster impressions of the collection. He declared them forgeries based on stylistic inconsistencies. Despite this, he praised their artistic merit as “the most beautiful you can expect to see in art.”

The signatures proved particularly problematic. Ancient artists from vastly different time periods appeared to work in identical styles. This impossibility became increasingly obvious to trained scholars. The gems’ provenance stories also contained suspicious gaps and contradictions.

Poniatowski published catalogs of his collection around 1830. These lavish volumes included detailed descriptions and illustrations. The publications were meant to establish scholarly credibility for the works. Instead, they provided evidence that would later expose the deception.

The Disastrous 1839 Auction and Its Aftermath

After Poniatowski’s death in 1833, Christie’s auctioned his collection in London. The 1839 sale proved catastrophic for the gem market. Half the collection remained unsold, while successful lots fetched prices far below estimates. The auction’s failure sent shockwaves through the collecting community.

John Tyrrell, a former private secretary, acquired 1,140 unsold gems as an investment. He commissioned scholar Nathaniel Ogle to examine the collection for a new catalog. When Ogle concluded many gems were recent forgeries, Tyrrell suppressed his findings. Instead, he hired James Prendeville and William Maginn to write favorable assessments.

The controversy deepened when Ogle published his critical analysis anonymously in 1842. Tyrrell responded angrily, defending Poniatowski’s character and the gems’ authenticity. This public feud further damaged confidence in engraved gem collecting. The Christie’s auction house had unwittingly facilitated one of art history’s greatest scandals.

Legacy and Modern Appreciation

The Poniatowski scandal had lasting effects on the art market. Collector interest in engraved gems plummeted for decades afterward. The episode highlighted the need for better authentication methods and scholarly oversight. It also demonstrated how reputation and social standing could shield fraudulent activities.

Today, surviving examples are valued as exceptional neoclassical artworks. Museums and collectors appreciate their technical excellence and historical significance. The gems serve as important case studies in art forgery and authentication techniques. They remind us that artistic merit and historical authenticity are separate considerations.

Many gems from the collection have been lost or scattered over time. Those that survive continue to fascinate scholars and collectors alike. The scandal transformed Prince Poniatowski from a respected collector into a cautionary tale. His legacy serves as a permanent reminder of the art world’s vulnerability to sophisticated deception.

The Poniatowski Gems scandal reshaped how the art world approaches authentication and provenance research. While the prince’s deception caused immense damage to the gem collecting market, it ultimately led to more rigorous scholarly standards. These beautiful forgeries continue to captivate viewers nearly two centuries after their creation, proving that artistic excellence can transcend questions of authenticity.