The Etruscan Terracotta Warriors stand as one of history’s most audacious art forgeries. These three imposing statues fooled the prestigious Metropolitan Museum of Art for over four decades. What seemed like priceless ancient artifacts turned out to be elaborate fakes created by a family of Italian craftsmen. The scandal that erupted in 1961 sent shockwaves through the art world and forever changed how museums authenticate ancient treasures.

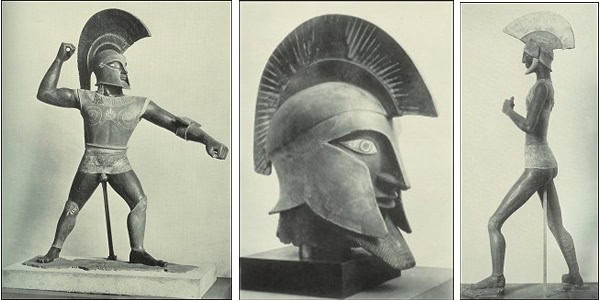

Between 1915 and 1921, the Metropolitan Museum purchased these towering terracotta figures. Each statue stood over six feet tall and appeared to showcase the artistic mastery of ancient Etruscan civilization. Museum experts believed they had acquired genuine archaeological treasures dating back thousands of years. The warriors’ imposing presence and seemingly authentic weathering convinced even the most discerning scholars.

But beneath their ancient facade lay a web of deception that would take decades to unravel. The true story behind these statues reveals a family enterprise built on artistic skill and criminal ambition. Their success depended on exploiting the art world’s desire for spectacular discoveries and the limited forensic tools available in the early 20th century.

The Riccardi Family’s Criminal Masterpiece Behind the Etruscan Terracotta Warriors

The Riccardi brothers, Pio and Alfonso, began their forgery career in the shadows of Rome’s thriving antiquities market. Italian art dealer Domenico Fuschini hired them to create fake pottery shards and ancient ceramics. Their workshop became a factory of deception, producing “ancient” artifacts that found their way into prestigious collections worldwide.

Their first major success came with a bronze chariot they claimed was discovered near an old Etruscan fort. The British Museum bought this elaborate fake in 1908 and proudly published their acquisition in 1912. This early triumph gave the Riccardis confidence to attempt something far more ambitious and dangerous.

The family enlisted sculptor Alfredo Fioravanti to help create their masterwork. Together, they crafted the first of the Etruscan Terracotta Warriors, known as the “Old Warrior.” Standing 202 centimeters tall, the figure appeared naked from the waist down with a missing left thumb and right arm. These deliberate imperfections made the statue appear authentically damaged by time.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased the Old Warrior in 1915 for a substantial sum. Encouraged by this success, the forgers immediately began work on their next deception. The “Colossal Head” followed in 1916, with experts believing it belonged to a massive seven-meter statue.

How the Etruscan Terracotta Warriors Fooled Museum Experts

Another fascinating historical case is: Piltdown Man: The 41-Year Hoax That Fooled the Scientific World

The third and final warrior proved the most ambitious of all. Designed by Pio’s eldest son Ricardo, who tragically died in a riding accident before completion, this statue stood over two meters tall. The Metropolitan Museum purchased it in 1918 for $40,000 and proudly displayed it as the “Big Warrior” in 1921.

The forgers’ technique was ingeniously simple yet effective. They sculpted each statue, applied glazes, then deliberately toppled them while still in an unfired state. This created authentic-looking fragments that could be “discovered” separately or reassembled as “restored” pieces. The fragments were then fired in smaller kilns, solving the problem of creating such massive pieces without industrial equipment.

Museum experts were completely fooled by the warriors’ appearance. The statues showed remarkably even firing characteristics, which one expert praised as evidence of superior ancient craftsmanship. The weathering patterns looked authentic, and the artistic style seemed consistent with known Etruscan works.

The three warriors were first exhibited together in 1933, creating a sensation among visitors and scholars. For nearly three decades, they stood as crown jewels of the museum’s ancient collection. Art historians occasionally expressed stylistic concerns, but without forensic evidence, their suspicions remained unproven theories.

The Scientific Discovery That Exposed the Etruscan Terracotta Warriors Fraud

The beginning of the end came in 1960 when chemical analysis revealed a shocking truth. Tests of the statue glazes showed the presence of manganese, an ingredient never used by ancient Etruscans. This anachronistic element provided the first concrete evidence that something was seriously wrong with these celebrated artifacts.

Museum officials remained skeptical until experts determined exactly how the statues were constructed. Joseph V. Noble, the museum’s Operating Administrator and self-trained ceramic archaeologist, conducted detailed technical studies. His investigation revealed the modern manufacturing techniques hidden beneath the ancient appearance.

The forensic evidence painted a clear picture of deliberate deception. The firing patterns, material composition, and construction methods all pointed to 20th-century creation rather than ancient craftsmanship. Still, the museum needed definitive proof before making any public announcements about their embarrassing mistake.

That proof came in the most dramatic way possible. On January 5, 1961, Alfredo Fioravanti walked into the US consulate in Rome and signed a detailed confession. The elderly sculptor revealed the entire operation, explaining how the family had created each warrior and sold them to unsuspecting museums.

The Shocking Confession That Ended an Era

Fioravanti’s confession contained one particularly theatrical detail that sealed the case. He presented the Old Warrior’s missing thumb, which he had kept as a personal memento of their successful deception. This physical evidence provided undeniable proof that he had been intimately involved in creating the statue.

The revelation sent shockwaves through the international art community. On February 15, 1961, the Metropolitan Museum announced that their prized warriors were elaborate forgeries. The admission represented one of the most embarrassing authentication failures in museum history.

The scandal exposed serious weaknesses in how museums evaluated potential acquisitions. The Riccardi family had exploited the limited scientific testing available in the early 1900s. They understood that visual inspection and stylistic analysis were the primary authentication methods used by experts at that time.

The art forgery scandal forced museums worldwide to develop more rigorous authentication procedures. Chemical analysis, microscopic examination, and other scientific techniques became standard practice for evaluating ancient artifacts.

The Etruscan Terracotta Warriors remain on display at the Metropolitan Museum today, but now as examples of masterful forgery rather than ancient art. Their story serves as a cautionary tale about the eternal battle between forgers and authenticators. These imposing statues continue to fascinate visitors, though for entirely different reasons than originally intended. The warriors’ legacy lies not in their supposed ancient origins, but in their role as catalysts for revolutionary changes in museum authentication practices.