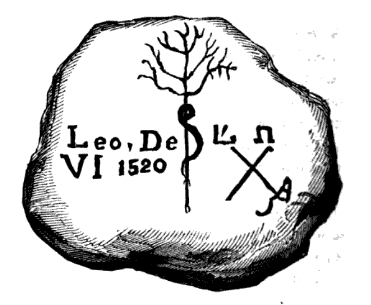

The Pompey Stone stands as one of America’s most successful archaeological hoaxes, deceiving scholars and historians for seven decades. In 1820, a farmer near Pompey, New York discovered what appeared to be a 300-year-old Spanish grave marker carved with mysterious symbols. The stone bore an inscription that experts translated as “Leo X by the Grace of God; eighth year of his pontificate, 1520,” complete with an image of a serpent climbing a tree. For the next 70 years, this elaborate deception would make fools of some of the nation’s most respected historians and antiquarians.

What makes this hoax particularly chilling is how easily it manipulated the scholarly community’s desire to find evidence of early European exploration in America. The stone seemed to offer proof that Spanish explorers had ventured far north of their known territories, perhaps dying alone in the wilderness centuries before anyone suspected their presence. But the truth behind this deception would prove far more sinister than anyone imagined.

The Mysterious Discovery of the Pompey Stone

Philo Cleveland was clearing meadowland on his farm near Watervale when his shovel struck something hard beneath the soil. At first, he paid no attention to the oval-shaped stone, roughly 14 inches long and weighing 127 pounds. It wasn’t until several days later, after rain had washed the dirt away, that Cleveland noticed the strange markings carved into its surface.

The gneiss stone bore an intricate inscription featuring a tree with a serpent coiled around its trunk. Below this image, carved letters spelled out what appeared to be Latin text. Cleveland, unable to read the inscription himself, brought the stone to local blacksmiths. Word spread quickly through the community about the mysterious artifact.

Visitors flocked to examine the stone, using nails and files to dig dirt from the carved letters. This amateur archaeology gave the inscription “somewhat the appearance of age,” according to later accounts. The stone’s weathered appearance and the difficulty of reading its inscription only added to its mystique. No one suspected they were looking at a deliberate forgery.

Scholarly Acceptance and the Pompey Stone’s Rise to Fame

Related article: Dancing Plague of 1518: When Hundreds Danced Themselves to Death in Medieval Strasbourg

The academic community embraced the stone with startling enthusiasm. Historians John Warner Barber and Henry Howe examined the artifact in 1841 and declared it authentic. They translated the inscription as a reference to Pope Leo X, dating the stone to 1520 during the height of Spanish exploration in the Americas.

The discovery seemed to rewrite American history. If authentic, the stone proved that Spanish explorers or missionaries had traveled much farther north than previously known. Some scholars theorized it marked the grave of a Spanish explorer who had died while searching for the Northwest Passage. Others suggested it commemorated a missionary who had lived among local Native American tribes.

The stone’s fame spread beyond New York. It was displayed for a year in Manlius before being moved to Albany, first to the State Museum of the Albany Institute, then after 1872 to the New York State Museum of Natural History. Scholars from across the nation came to study what they believed was one of America’s most important archaeological discoveries.

Strange Alterations and Growing Doubts About the Pompey Stone

By the 1890s, careful observers began noticing disturbing changes to the stone’s inscription. The date “1520” had somehow been altered to read “1584,” and the letters “L on” had mysteriously disappeared entirely. These unexplained modifications raised uncomfortable questions about the artifact’s authenticity.

In 1894, antiquarian William M. Beauchamp conducted the first serious investigation challenging the stone’s age. His research revealed inconsistencies in the carving technique and questioned whether the inscription matched genuine 16th-century Spanish work. Beauchamp’s findings suggested the stone was a much more recent creation.

The mystery deepened when New York state archaeologist Noah T. Clarke attempted to restore parts of the inscription in 1937. He found that many crucial records had been destroyed in the 1911 New York State Capitol fire, making it impossible to trace the stone’s early documentation. The missing records seemed almost too convenient for a genuine artifact.

The Shocking Confession That Exposed the Truth

The hoax finally unraveled when John Edson Sweet published a letter in the Syracuse Journal in 1894. Sweet revealed that his uncle Cyrus Avery and Avery’s nephew William Willard had carved the stone decades earlier “just to see what would come of it.” The two men had buried their creation in Cleveland’s field, never imagining it would fool the academic establishment for so long.

Sweet explained that his relatives had decided not to come forward after the stone began attracting serious scholarly attention. They watched in amazement as respected historians and antiquarians proclaimed their crude hoax a genuine archaeological treasure. The longer the deception continued, the more difficult it became to admit the truth without facing serious embarrassment.

The revelation sent shockwaves through the archaeological community. Scholars who had staked their reputations on the stone’s authenticity found themselves humiliated. The incident became a cautionary tale about the dangers of wishful thinking in archaeological interpretation and the importance of rigorous scientific analysis.

Today, the Pompey Stone remains on display at the Museum of the Pompey Historical Society as a reminder of one of archaeology’s most embarrassing moments. Remarkably, even after the confession, some continue to argue for its authenticity. The stone serves as a chilling example of how easily experts can be deceived when they desperately want to believe in a discovery that confirms their theories about the past.