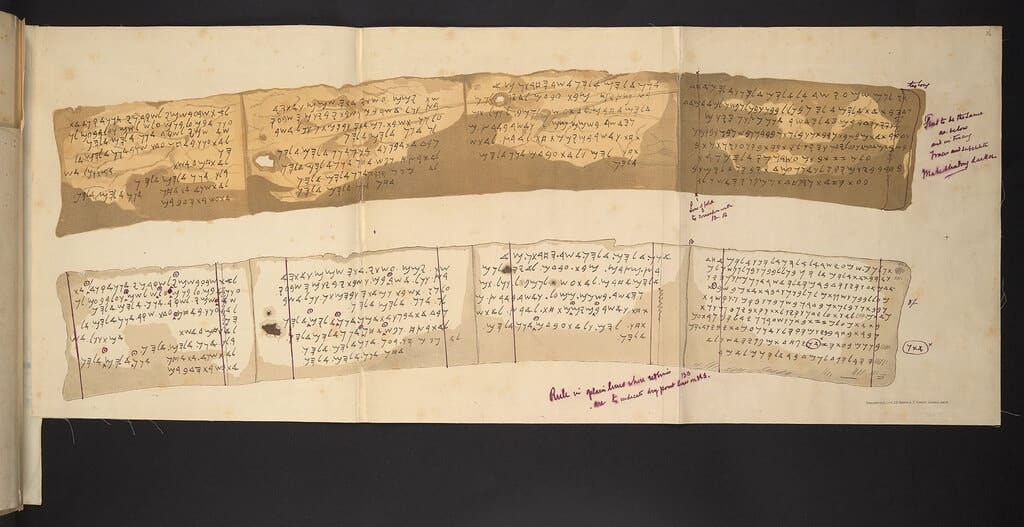

The Shapira Scroll remains one of biblical archaeology’s most haunting mysteries. In 1883, Moses Wilhelm Shapira presented fifteen leather strips inscribed with ancient Hebrew text to European scholars. The manuscript contained what appeared to be an early version of Deuteronomy, complete with an eleventh commandment that read: “You shall not hate your brother in your heart: I am God, your god.” Within months, experts denounced it as a forgery. The shame of this accusation drove Shapira to take his own life in 1884. Yet the scroll’s true nature continues to baffle researchers today.

The manuscript’s discovery story reads like something from an adventure novel. Shapira claimed Bedouins found the strips in caves near the Dead Sea around 1878. They had been fleeing enemies and sought refuge in high rocky caverns overlooking Wadi Mujib. Inside, they discovered bundles wrapped in ancient linen. Thinking the packages might contain gold, they tore away the fabric. Instead, they found only blackened leather strips covered with strange markings. Most threw them away in disgust. One Arab kept them, believing they brought good fortune.

The Shapira Scroll’s Disturbing Contents

What made the Shapira Scroll so unsettling wasn’t just its age. The text differed dramatically from known biblical manuscripts. It contained only the Ten Commandments and narrative portions, lacking Deuteronomy’s extensive legal code. Most shocking was that mysterious eleventh commandment about not hating one’s brother. No other biblical source contained this addition.

The manuscript presented the commandments consistently in first person, as if God himself was speaking directly to readers. This stylistic choice felt eerily personal compared to traditional biblical texts. The leather strips themselves appeared ancient, blackened with age and inscribed in Paleo-Hebrew script. Yet something about them troubled the scholars who examined them in 1883.

Christian David Ginsburg, a leading biblical expert, spent weeks analyzing the fragments. He noted inconsistencies in the Hebrew script and questioned certain word choices. The Biblical Archaeology Society reports that Ginsburg ultimately concluded the entire collection was an elaborate fake.

Why Scholars Rejected the Shapira Scroll

Another fascinating historical case is: Persian Princess: The Archaeological Hoax That Fooled the World in 2000

The academic community’s swift rejection of the manuscript stemmed from several troubling factors. Shapira provided multiple, contradictory accounts of how he acquired the strips. In one version, a Bedouin named Selim brought them to his shop. Another story involved a meeting with Sheikh Mahmud el Arakat and various tribal members. These inconsistent narratives raised immediate red flags.

Experts also questioned the manuscript’s physical properties. The leather appeared too well-preserved for something allegedly found in desert caves. The ink showed unusual characteristics that didn’t match known ancient writing materials. Most damning, the Paleo-Hebrew script contained what scholars considered modern mistakes.

The timing seemed suspicious as well. The discovery occurred during a period when biblical archaeology was experiencing unprecedented public interest. Forgeries were common, and dealers like Shapira faced enormous pressure to produce sensational finds. The financial incentives were substantial – Shapira initially sought £1 million for the collection.

The Shapira Scroll’s Mysterious Disappearance

After Shapira’s suicide in 1884, the manuscript’s trail becomes murky. His widow retained at least portions of the collection, sending some fragments to German scholar Konstantin Schlottmann. The strips later appeared at a Sotheby’s auction, where bookseller Bernard Quaritch purchased them for just £10 5s.

Contemporary newspaper accounts reveal that Dr. Philip Brookes Mason displayed “the whole of” the scroll during a public lecture in Burton-on-Trent on March 8, 1889. After Mason’s death in 1903, his possessions were sold off and the manuscript vanished completely. Despite extensive searches by modern researchers, the current whereabouts remain unknown.

This disappearance has only deepened the mystery surrounding the collection. Without the physical artifacts available for modern scientific testing, debates about authenticity continue to rage. Carbon dating and advanced chemical analysis could potentially resolve the controversy once and for all.

Modern Theories and Ongoing Investigations

Recent scholarship has challenged the century-old consensus that dismissed the manuscript as fake. Biblical scholar Idan Dershowitz argues that the strips may indeed be authentic ancient texts. His analysis suggests the Hebrew script matches writing styles from the First Temple period, potentially dating to the 10th century BCE.

Dershowitz points to subtle linguistic features that would have been nearly impossible for a 19th-century forger to replicate accurately. The manuscript’s theological differences from known biblical texts might actually support its authenticity rather than undermine it. Ancient religious documents often contained variations that were later standardized.

In March 2024, Dershowitz claimed to have discovered a Genesis fragment with identical stylistic features and shared provenance with the original strips. He promised carbon dating results would soon resolve the authenticity question. As of late 2025, however, no test results have been publicly released.

The search for the missing manuscript continues. Researcher Ross K. Nichols has traced the collection’s ownership history and believes he’s close to identifying its current location. If found, modern scientific analysis could finally determine whether Moses Wilhelm Shapira died defending a genuine archaeological treasure or an elaborate deception.

The Shapira Scroll controversy represents more than just academic debate. It highlights the dangerous intersection of scholarly reputation, financial pressure, and the human cost of being wrong. Whether authentic or forged, this mysterious manuscript claimed at least one life and continues to challenge our understanding of ancient biblical texts. Until the strips resurface for proper testing, their true nature remains one of archaeology’s most compelling unsolved mysteries.